Sepoy Saif Ali: Commemorating the Legacy of an Indian Soldier in World War I – My Grandfather’s Story

Last weekend, it was Remembrance Day in England, that ostensibly solemn time of the year when all its roads, churchyards, war memorials and people’s lapels become blazoned with bright red poppies. Although poppy wearing has become less fashionable in recent years, especially among the younger generations, the poppy still holds a sway over public imagination. Within a few days, the poppy changes the mood in the country. And people wearing poppies walk with some gravity, slowly gliding by you with their umbrellas and proud lapels, wanting you to gaze at the poppy, as if the flower on their lapel is a portal to the past. Or as if each poppy is a face of a fallen soldier, peering at posterity from some faraway constellation. As if you looked hard enough at the poppies, you could tell their age, their demeanours, their accents.

The poppy has come to symbolize a number of things for different people. For some, it’s the remembrance of some 9-10 million soldiers who perished in the war; for others, it’s about collective guilt and unspeakable cruelty of recruiting 15/16 year old boys and sending them over to certain death. Yet for others, it’s about remembering the consequences of the most senseless and important war in history. All our current geopolitical problems, including the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict, go back to WW1. Whether we like it or not, we are all implicated in its history, all children of that senseless tragedy.

I have an instinctive dislike of the poppy, for the kind of remembrance it symbolizes hides more than it reveals. It hides, for example, the war contribution of millions of colonial soldiers from India without whom the Western Front could not have been won. And it’s the kind of sanitized symbolism—cleansed of the traumatic memories of the British Empire—that will instinctively appeal to fascist minds. The hallmark of a fascist mind is its tendency to look for purity in the past, the cleansed out memory of the past which is being attacked by a messy present.

Over the years, the poppy has come to symbolize something entirely different for me than its popular meaning. It has come to symbolize historical invisibility, erasure and shame. Every November, when I see poppies, I think of my grandfather, sepoy Saif Ali, who was a veteran of WW1 and one of the 1.5 million Indian soldiers recruited by the British Empire to fight on the Western Front. Some 74000 of them died and some 67000 wounded, including my grandfather, who took a bullet while fighting Churchill’s infamous Gallipoli campaign.

Silenced Histories: The Indian Soldier in World War I and the Erasure in Collective Memory

An Indian Soldier in World War I, like my grandfather cut a lonely figure on historical landscape, for the Indian soldier of WW1 is a doubly forgotten figure. He has no place either in the collective memory of England or the Indian subcontinent. The English prefer not to remember him—at least not often enough to make him part of their collective memory—as it undermines their nationalist narrative of blood and soil soldier, the image of English Tommy in the trenches, going over the top for a terrible but necessary tragedy. In this way of remembering, the Indian soldier becomes a silent subaltern figure. To acknowledge his presence in the history of WW1 would be to acknowledge the enormous contribution of the non-white, non-English soldiers to the British war effort. This invisibility of the Indian soldier has been blatantly reiterated in the centenary commemorations over the past decade. Since 2014, books, movies, TV documentaries and public history lectures about WW1 have overwhelmingly remembered only the English soldier. It’s always a Tommy’s face peering out of that poppy, never of a Jawan from the Indian subcontinent.

For people of India and Pakistan, an Indian Soldier in World War, is a source of shame and treachery and hence best consigned to the dustbin of history. From their perspective, he was fighting the wrong war, the white man’s war, against people who had not attacked or threatened them. Additionally, he was fighting against the Ottoman Empire, the last Muslim empire, and thus hurt feelings of the majority of Indian Muslims who sympathized with the Ottomans. Thus to remember him is to continue the legacy of colonialism, to give imprimatur to the narrative of the colonizer that only their wars matter and the history of colonizer ought to be the universal history of the world. It complicates their sense of generational trauma. After all, 1.5 million of them went to Europe to fight one white man’s war against another white man.

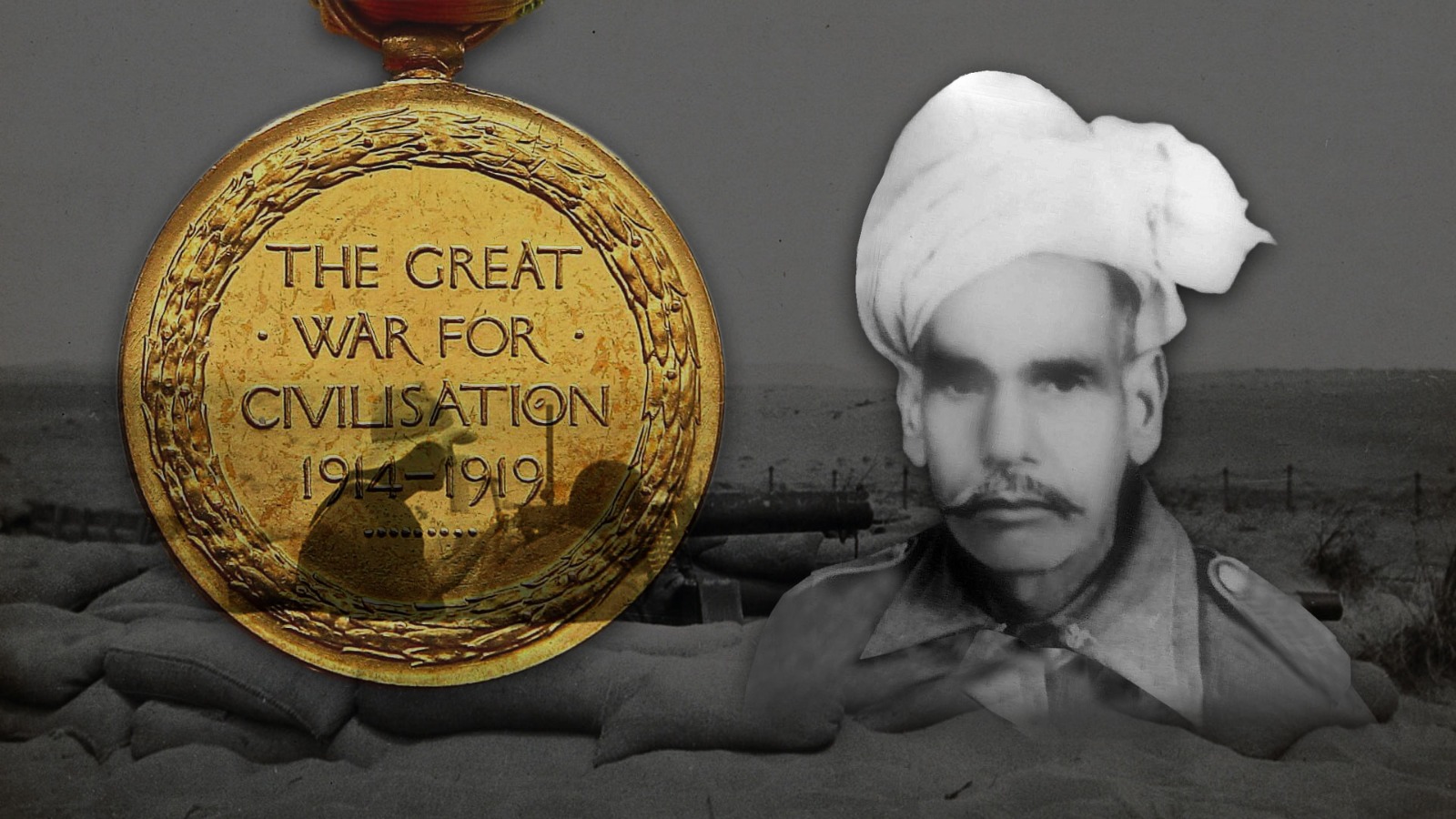

My grandfather died before my father was even married, so I know precious little about him. But combining family stories and some archival research at Kew Gardens, I’ve pieced together a basic sketch of his life. He was recruited as a sepoy in the 29th Indian Brigade of the British Army when he was a boy of 15/16, first stationed at Port Said in Egypt, and then recruited to be part of Churchill’s ill-fated Gallipoli campaign against the Ottomon Empire. In late 1916, he was back in Rawalpindi and seemed to be in good graces of his officers. By the end of the war, he had bought more land near his village, perhaps using the savings from his income. The next we hear of him is in the 1940s. He is now a police officer in Peshawar, and comes back to see his wife and children in his native village a few times a year. His eldest son is running the farm business and looking after the family. On one of his visits back to the village, he learns that his oldest son, a 20-year-old boy, had been murdered in an old blood feud. Shocked and despondent, he retires and becomes detached from life in general, only animated by the sight of his youngest son, my father. That is all I know of him. There are no letters and other archival materials to piece together his life. All he’s left behind is this Victory Medal, a broken Swiss watch and his only (known) photo. Like millions of other Indian soldiers in WW1, his war experience is permanently lost in the mist of history. He was one of Churchill’s thousands of soldiers who fought at Gallipoli and two thirds of whom perished in the trenches, their bodies buried where they fell. No religious rites were performed. No one knows their names.

So how do you rescue the memory of an Indian Soldier in World War I, like my grandfather from the shadowlands of history? Imagination seems the only weapon to resist the violence of archival forgetting.

Jhelum to Egypt: Tracing the Journey of Sepoy Saif Ali

So this weekend, I went to the Oxford War Memorial, lit a candle for my grandfather and all the dead soldiers from the subcontinent. Then I came home and spent a moment of silence with my grandfather’s monochrome (his only known photo) and some tokens of remembrance from his WW1 days. I rummaged out his slowly fading bronze Victory Medal and his broken Swiss pocket watch from the family heirlooms and tried to imagine what his personal experience of war would have been like, the experience which the English exceptionalists refuse to acknowledge (although there are signs of some progress in the younger generation).

I imagine his experience as a boy of 16, an awkward teenager, prone to emotional outbursts, really a child in the body of a man. What would have initially prompted him to join this dangerous venture to far-off lands? Money, of course, would have been an important factor, but I suspect other, psychological factors played a more important role, as they often do in the arrogance of youth. I suspect the dress of the British soldiers made an impact and was a key motivating factor. He would have felt different, ‘cooler’ wearing that uniform, proud of the long collared crisp khaki shirt, the loose breeches at the waist tightened by puttee up to his knees. He would have stood proudly in the village in the uniform, a gingerly Indian village boy transformed by modern Western clothes. More than anything, it would have been this ‘cool’ factor and the sense of adventure in far-off unknown lands which would have prompted him to join the British Army in the first place. Perhaps, he was playing the part that colonists assigned his people. The British Army recruited heavily from this region as they considered the peopl of Jhelum to be ‘martial races’. By joining the army, my grandfather could validate this narrative about his people. ‘Yes, we are the martial race. We fight wars. Look at the buildings of King Porus. Look at the graves of Alexander the Great’s soldiers buried here.’

No doubt, family dynamic played a role. As the youngest son, he knew that the lion’s share of the family farm would have gone to his older brother. No doubt his father would have encouraged him to venture out in the world to find his fortune. Perhaps this army adventure will give him his fortune. His mother would have disagreed but silently complied. Wondering if her son would ever return, she went on a pilgrimage to the shrine of the local saint, set on a high promontory. There, she lit a lamp for his son and tied sacred threads on the old banyan tree. Then she made an amulet, a ta’wiz, for him, by writing obscure magical numbers and Quranic verses on a small piece of paper and sewing it inside a small leather pouch. She then put the amulet around his neck as a pendant, tied the knots tightly and raised her hands as he took first steps on the long journey from Jhelum to Port Said, Egypt.

Silent Struggles in the Trenches, Untold Challenges of the Indian Soldiers in the World War

As an Indian Soldier in World War, Much of his time in Egypt would have been spent in the trenches, doing war exercises, the tedious morning drills. The putrid air of the trenches would have been unbearable initially. He’d sit behind a wall of sandbags, one knee on the ground, carefully balancing his Lee-Enfield rifle on his right shoulder, concerned if his big bulky turban was exposing him to the enemy fire. His fellow sepoy, perhaps a young Hindu boy called Moti Lal, would be kneeling next to him, holding a periscope and binoculars, scouting for the enemy moves and giving him instructions. When holding the position, he would not only be at the mercy of enemy artillery, but also non-human creatures. A little army of red desert ants would march through the cracks in between the sandbags. Some stray ants would find their way up his pants and bite, distracting him from his targets. Little desert rats would run in from the gaps between the sandbags and rampage through the leftovers. There was a rumour going on in the trenches that the rats were being deliberately sent by the enemy to spread disease and infection, perhaps even the bubonic plague. At times, he’d scratch the trench wall with his gun and disturb some nocturnal desert creature. A scorpion would creep in through a crevice, stand in front of his nose, and obscenely raise its long concatenated tail, as if openly challenging him to a duel. Then, a barrage of artillery fire would land near the sandbags, followed by machine gun fire. When the silence settled, he’d feel alone and exposed. Now there were new holes in the sandbags. The scorpion had disappeared. The rats were quiet. He could only hear his own tinnitus. In silence, he could see that the red ants were still marching relentlessly forward in a single file, crossing over any hurdle in their way. Their new hurdle was the body of Moti Lal, which they marched over with the indifference of a mechanical automaton.

The burial of his fellow Hindu and Sikh soldiers in the trenches would have caused some commotion for an Indian Soldier in World War. They were supposed to be cremated, not buried. But cremation in a Muslim country like Egypt would have been a taboo. It would have been unacceptable to the natives. The Nile is not the Ganga, the locals would have reminded them, just bury your dead in the sea. My grandfather would have initially refrained from touching the body of a Hindu soldier for the fear that some Hindu soldiers might be offended. But then he would have taken the first step and tried to lift the body when the English officer would step in to stop the cremation. The cremation could not go on, he would have told them in his affected received pronunciation, because the enemy would judge their position from the smoke.

From time to time, he’d clutch his mother’s amulet, the little black leather pouch, and look back expectedly at the bunker towards the English officer. The English officer would be busy at the telegram machine, deciphering the strange beeps and blips. What will his wretched machine say now? Can they finally move Moti Lal’s body? ‘No, hold the line’, the officer would signal with his hands. He’d go pick up Mot Lal’s binoculars and start scouting the enemy, punctuating this regime by nervous cigarette breaks. In the dykes dug within the narrow passages and valleys, the sound of constant shelling would have rattled his brains. A soldier fell next to him and had to be buried there. For years after the war, he was puzzled when people in his village did not smile back at him. He thought they held a collective grudge against him because of his new experience of the far-off lands, or somehow he had offended them inadvertently. He never knew he was only smiling in his head. He had this affixed shell-shock look, as though his expressionless eyes were the permanent mask that trench warfare put on his face.

In this new unfamiliar world, his first and biggest problem would have been food. Initially, he would have refused to eat the canned food altogether. He would have refused to acknowledge the strange bits of meat floating inside a metal can as food. What is this? A sealed metal can with cold beef and corn in it. Some biscuits and jam in a tiffin. Cold tea brought in petrol cans and grudgingly poured into white enamelled cups. He might have been reassured by the officers that the food was halal, but he wouldn’t have believed them. He would have waited for the next meal, hoping to get freshly made chapati, perhaps with some dal and vegetables. And then the next meal, and the next one, until he would have finally swallowed a spoonful of cold baked beans.

Within the narrow confines of the trenches, the social and ethnic differences would have become magnified. How did he manage to overcome the language barrier with his fellow soldiers speaking at least a half dozen languages? To break ice with the Gurkhas, the Burmese, the Baluchis, and other soldiers, he would have devised an elaborate game of charades. With a set of exaggerated gestures, he would have made some essential communication. Small talk was probably peppered with some random English and Urdu words. Together, the soldiers would have invented a kind of secret language. They probably relished the fact that tje English officers could not understand this new global language of the trenches. The subaltern had a way of speaking. He had agency to test the nerves of the English officers. Letters of soldiers from the archives show that most of them already knew their letters were being censured by the British officers. To avoid this, they used a code language to communicate with each other and with their friends and relatives back in India. For example, ‘black pepper’ was the codeword for Indian soldiers and ‘red pepper’ meant British soldiers. So when they wanted to warn their friends about more recruitment of soldiers from India, they would write ‘black pepper is in high demand in England’.

As a Muslim, he was supposed to perform ritual prayers, if not five times a day, then at least once a day, or even once a week. But where could he get clean running water to do ritual ablutions before the prayers? Was it uncomfortable to pray under the watchful eyes of others in the small narrow pits? Is it an appropriate place to pray at all, he would have thought. The stink and fume of the trenches, the corpses thinly buried under their feet, the sound of artillery, all would have made an unseemly and unholy occasion for ritual prayers. Perhaps he only prayed silently. Or he didn’t pray at all. Instead, he kissed the amulet his mother gave him, the protective Quranic verses sealed inside a small leather pouch. Allah would understand. When thinking of his own death in the trenches, he remained worried about one thing: how would he converse witht the angels of death for he knows no Arabic and the angels would surely talk in Arabic. Or perhaps, at that tender age, he experienced the first loss of religious innocence and, as he looked up, he understood the meaning behind the unforgiving silence of the heavens.

When posted on night duty, he must have entertained a stray rebellious thought: desert now under the cover of night and never look back. Perhaps some rank and file soldier crawled up from the bunker in the dead of night, lowered his dimly lit lantern, and whispered an outrageous mutiny plan in his ear. He was enticed for a moment. ‘We could pose as pilgrims to Mecca,’ the other sepoy would have whispered. ‘We could pay someone to get safe passage cards, and board a merchant navy ship to Karachi.’ But then the silhouette of a burly figure appears from the bunker, some senior sepoy with a white beard says in hush but angry voice: ‘ Do you not remember Kala Pani? The Cellular Jail?The taboo banishment to Kala Pani, the unholy waters that would stigmatize not only him but his entire village back home forever. Surely, a valiant death in the trenches is far more valuable than the shame of Kala Pani. Shame, that defining fear of the subcontinent, would have caused a moment of silence in the trenches. Another round of artillery fire from the Ottoman would have ended the whispering campaign.

Of Victories and Valiance: A Soldier’s Journey Home from War

Surely, for that teenager, there was excitement and entertainment during the rest days. Did he spend his rest days playing cricket with other Indian sepoys? Perhaps he went to Alexandria or Cairo and discovered the magical new technology called the motion picture. There, sipping qahwa with his fellow sepoys, he watched the pantomimes of one Mr. Chaplin, the ghostly animated figure moving across a white screen. Perhaps he saw Making a Living, and felt surprisingly entertained that he could decipher a story without a language. Afterwards, he and other sepoys imitated Mr. Chaplin’s body language and found it immensely amusing. Then they went to a late night cabaret to smoke sheesha, where they were all mesmerized by the performance of a famous Egyptian belly dancer. Perhaps he fraternised with the local Muslims at the Cairo mosques and madrassas in broken Arabic and talked about how he felt fighting against his co-religionists for the British. Perhaps an elderly imam leaned in and said ‘Son, this war has nothing to do with us.’

Unmoored from his familiar surroundings, the sea would have added insult to injury. For the first time in his life, the boy would have found himself not trusting his feet. Floundering through the cold wet drills on the sea deck, there would have been one thought constantly hanging over his head: he did not know how to swim. And as soon as he found his sea legs, he needed his land legs back as they were now being forced to make a landing. The Ottoman sea mines were sinking the British fleet, so they had to land and dig trenches again, this time on the seashores of Cape Helles, Gallipoli. Churchill’s strategy to breach the Dardanelles straits–the ‘soft belly’ strategy–had ended in a spectacular disaster, sinking submarines and battleships and risking lives of thousands of Indian troops. The Ottoman forces had set up traps at key point throughout the straits. Who is this deranged Mr. Churchill, who are his stupid teachers, what school did he go to, my grandfather would have thought as he would have finally realized that he had signed his life away to be cannon fodder for bad military strategists. It was there, in the trenches of Gallipoli, watching the British battleships sinking on the one side and the Ottoman artillery fire on the other side, that he was hit by a machine gun bullet in his shoulder. As he lay on the ground and his field of vision slowly faded, he could see that some of the sepoys lying next to him were already dead. No one would pick our bones, he thought. But how would I converse with the angels with no knowledge of Arabic, his last thought as he faded into a slow black emptiness. Later on, when the war ended, children from local Greek villages would roam around the same trenches, collecting skulls and bones of Indian sepoys in the hope of selling them as war memorabilia. If you go to Gallipoli now, you can see the graves of Indian soldiers there.

The next thing he remembered was the face of a nurse in a rescue ship that was transporting him back to Egypt. Despite the injury, the next few weeks were the most pleasant moments of war for him. He was gently tended to by the nurses and had never been treated with such kindness, even reading literature and poetry to him.

A few months later, he was on a train back to his village. On his way, he stopped in Lahore and bought a Swiss pocket watch (pictured here) from a diamond jeweler called ‘Minck’. He was now the first man with a watch in his village.

But going back to this small adobe village of a hundred people would have been confusing as an Indian Soldier in World War. Did he really belong there anymore? There was world out there that wasn’t even available to the imagination of his folks back in the village. Now that he had seen this bigger, brighter world, would he ever be able to live in the village with some satisfaction, or even if he lived there, would he ever feel settled and anchored again? He stayed in the military after his recovery, changing posts occasionally and living in various cities around the country, before coming back to his village in old age and sending his youngest son, my father, to the military of a new country. Why send the new generation to the military again? Because that’s what you do.

In the end, I imagine what would he make of Europe and Britain if he had been alive today. I think of the inscription on his war medal “The Great War for Civilisation” and I think of him (an Indian Soldier in World War I) in a boat to Europe, to save Europe from itself.

I think of sinking boats in Battle of Gallipoli. And I juxtapose that image to the boats sinking off the coast of Greece and Italy these days, boats full of people from the former Empire, people portrayed as posing threat to the very same civilization that their ancestors helped save, and how they drown on the shores of Europe.. I’d rather have the symbol of sinking boats in the Mediterranean than poppies as a symbol of remembrance.

*Story of Sepoy Saif Ali: An Indian Soldier in World War I